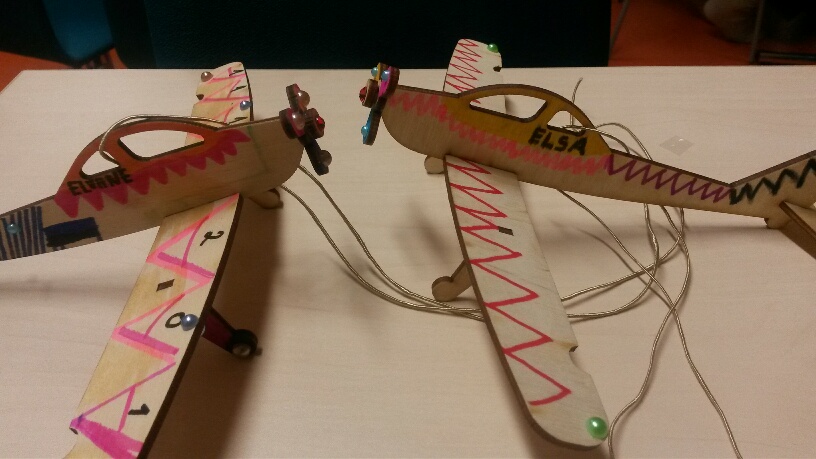

In a school in Tallinn last week, we made planes with the children and their fathers. The twin girls named their planes Elsa and Elviine. I thought they were girls’ names, but it turned out that Elsa and Elviine were the first female pilots in Estonia. A few days later, I started researching the matter and discovered a fascinating story about Elviine Kaalep, who was indeed one of the first female pilots. She was a girl from Tallinn, Nõmme, with a fascinating life story. Her story was published in the magazine Kultuur ja Elu 2/2005, and we decided to bring it to you on our blog. Have fun reading with your children!

The tumultuous life of Elvy Kalep

Culture and Life magazine 2/2005 WRITER:HEIKI RAUDLA

When Heiki Raudla read Anto Juske’s story about Estonia’s first female pilot in Sakala in January 2005. Elviine Kalepist, he remembered that there was something about him somewhere in the archives at home. While browsing through the material, he became interested in finding out more, and so the story of a woman who went by the name of Alviine or Elviine Kalep (Kaalep) in Estonia and Elvy Kalep abroad was put down on paper.

As the church records show, Alviine (Alwine)-Johanna Kalep (Kaalep) was born in Pärnumaa, Tori parish, Taali parish on 26 June 1899 (dd). Her father Aksel (Axel) Emil (b. 9.03.1875) was from Jäneda and was a locksmith, her mother Joanna (b. Liidemann) was born in Tori parish on 28 April 1979. Aksel and Joanna married on 6 September 1898.

Elvy was the only child of the family. Records of her long and complicated life, full of legends, were not easy to find and some are contradictory. Moreover, some of the facts come from the press, and in many cases the question arises as to where there is truth and where there is not.

Escape to the East

- In 2008, a long story about Elvy Kalep appeared in the Florida newspaper The Naples Daily News. It says that she was barely a year old when both her parents died. Kristin’s relatives, who lived on Tähe Street in Nõmme, Tallinn, adopted her into their family. She was a talented girl, but of a restless nature. Even as a small child, she ran away from home to the wide world. However, she was caught at the Baltic station. At the age of eight, she took up drawing and cartooning. After completing her primary education, Elvy went to Tallinn Girls’ Commercial Gymnasium. There, the teachers noticed her bohemian nature and talent, and thought that she would be the talk of the town one day.

In 1916, Elvy was sent away from the war, first to Narva, then to St Petersburg, but it was there that she was caught up in the revolution. Kalep later described his experience of the revolution as follows. On the other side of the river, on the bank of the river, we were watching a parade of people on the riverbank. To get a closer view, we both climbed the rampart that bordered the bridge and from there we saw the beginning of the revolution. At the end of the bridge there was a large, unruly crowd, a line of soldiers moving, armed cavalry policemen and Cossacks armed with spears and swords. It was the latter who rode back and forth energetically and proved to be the most active in the task of keeping order.

Somehow, one of the horses backed up against a lamppost and stumbled to the ground with its rider. The man crashed into the kerb and his rifle went off. Hardly had the accidental bang sounded when the crowd literally went mad, apparently thinking that the horseman had fired on the crowd. A half-naked man lying in the street was then attacked and the man was literally mauled to death.”

The following night, riots broke out on a wider scale and terror, brutality and hunger set in. As Elvy happened to be a witness to the events, he had to spend the night in a police detention centre.

It took nearly eight years before Elvy was able to get out of revolution-hit Russia.

Initially, though, all those who had expressed a desire to escape the revolution were ordered to spend the night in a railway station. More than 20,000 of them gathered there. But it took another month or so before they could move. The evacuation, however, did not take place westwards towards Estonia, but eastwards. One of the reasons for this was that Elvy and his step-aunt were supposed to have a brother somewhere near Vladivostok. They were in for trouble near Lake Baikal. A train was sent back from the district a total of eight times, and it was only on the ninth occasion that the fugitives escaped.

Elvy Kalep becomes secretary to Chinese Marshal

When they finally reached Vladivostok, it turned out that their relative had left for China. In Vladivostok, Elvy met a Russian general, Count Slavchev. The two fell in love, then married and had a son. In the Far East, Elvy succeeded in graduating from a commercial high school there. After several attempts to cross Siberia to Estonia and return from the Ural borderlands, they decided to flee to China, where the Russian general had connections with the Chinese strongman Chang Tso-Lin. In the outbreak of revolution and civil war, the family fled to China, leaving behind their possessions.

The first refuge was found in Harbin. The child could not withstand the deprivation and died at the age of one. In the confusion, the man disappeared a year later. However, Elvy’s language skills saved him and he was recruited as an interpreter. Thanks to his talent and good language skills (Russian, German, English and Chinese), he was initially employed as an interpreter for a British general in Mukden (Shenyang). The general had a large arsenal of weapons in Mukden.

Civil war had also broken out in China and the warring generals needed weapons. The ruler of northern China, Marshal Chang Tso-Lin (1873-1928), saw the need for a private secretary. His offers outstripped the Englishman’s, and Elvy became private secretary to the powerful marshal, later the latter’s son, Chang Hsüeh-liang or Zhang Xueling (1898 or 1901-2001).

Elvy, however, was somehow drawn to aviation. In 1924, the first flight in China was to be made in the English Bristol Fighter (one of the most distinguished military aircraft of the First World War). When the plane crashed a few hours before the scheduled flight during a test flight by a Chinese pilot, Elvy decided that if flying was still so dangerous, it was wise to wait. He later explained his interest in aviation and engineering by the fact that he was the only child of his parents and his father was trying to raise him as a boy and his mother as a girl. In fact, he became interested in flying when he was still at commercial high school in the Far East. Later, in 1950, he explained his reasoning. For thousands of years people have longed to fly and have not been able to. Now, for once, it is possible, and why not try to join in.”

His credo was like an African proverb: life must be taken with a big spoon.

Elvy gets pilot papers

- In 2007, Chang Hsüeh-liang sent his secretary to Europe on holiday. But Elvy had a fancy for life among the wide-eyed Chinese. He and his aunt finally reached Tallinn in 1926, by a rather difficult route (through Sumatra, Italy and France). She stayed with her foster parents for a while before moving to Paris. In Paris, the pretty and energetic woman began to study oil painting with the famous portraitist Alexander Yakovlev, and in the winters she took up bobsleigh racing in Switzerland (where she even won the championship once) and car racing.

When she visited her foster parents again two years later, she had already established a new career. In Paris, he had married Baron Rolf von Hoeningen-Bergendorff and obtained Austrian citizenship. Her husband was very wealthy and probably German or Austrian by nationality. In the winter resort of St. Moritz in Switzerland, the famous Dutch-born aeronautical engineer Antony Fokker (1890-1939) saw Elvy’s virtuoso skiing and advised her to learn to fly. (According to other accounts, Fokker’s eye was already drawn to the energetic and ambitious female student, whose courage and perseverance appealed to him). Elvy’s studies were not even hampered by the fact that she had broken her right wrist in a sledging accident in the winter of 1931. Fokker, for his part, encouraged her to fly and treated her as his favourite student, with the result that after only five hours of flying (the minimum number of hours required at the time – H.R.) Elvy passed the necessary exams on 1 August 1931 and became the first Estonian woman to receive a professional pilot’s certificate (No. 369, she was the seventh female pilot in Germany with papers). At the same time, she also learned about aircraft engines and was soon free to work as a mechanic. “At that time I was flying a Klemm-Mercedes (specifically a Klemm L2bIIc (D-1132)) and I could dismantle and reassemble the engine of my plane in my sleep,” Kalep confirmed in an interview in 1971.

Flyer with lipstick

In 1931, while in Germany, he flew to North Africa, Asia and European airspace. In a later interview he mentioned. In August of the same year, Elvy Kalep and his mechanic Valter Mayer started a flight with the sports plane Klemm (named after the designer-engineer Hans Klemm) on the route Berlin-Stettin (Szczecin) -Danzig (Gdansk) -Kaunas-Miitavi (Jelgava)-Ria -Tallinn. Already at the beginning of the flight, the plane was caught in a thunderstorm and rain and had to land there. Kalep also had to make a few bad landings later. At Miitavi he had to get lost in a thunderstorm and again had to make an emergency landing. This time the propeller of the plane broke during landing. After the emergency landing, curious Latvian peasants had found Elvy sitting under the wing with a mirror and a lipstick. Elvy’s flight baggage was very meagre at all: a toothbrush and a few other necessities. Perhaps that’s why European journalists called him a pilot with a lipstick. She flew from Riga to Tallinn in an hour and 50 minutes, arriving at Ülemiste Airport at 18.50 on 18 August 1931. There he was met by his hosts and journalists. On 20 August 1931, the newspaper Oma Maa wrote. The aircraft was made by Klemlemlem Klemmer, a factory of the Klemmer factory. The plane was made by Klemmi, a Klemmi factory, with two seats. It was the Klemmi airplane. When he landed, a young man, a German (Valter Mayer – H.R.), sat in the pilot’s seat. The famous female pilot was met at the airfield by air marshals and a number of air force officers and their wives. There were few other private persons at the reception. Red flowers were presented to the female pilot. Mrs. Kaalep herself immediately drove to Nõmme, where her relatives lived. From Estonia, Mrs Kaalep wants to fly to Finland and from there to Brazil to make a sightseeing flight with some other pilots and possibly penetrate unexplored areas of the Brazilian jungle. In Tallinn, Elvy visited her foster parents. She also had the chance to visit Mari Raamoti, the chairwoman of the Estonian Women’s Defence Corps, who presented her with a home defence badge, the Minister of Roads, the Minister of Defence and the head of the Defence League. On 19 August, he started his return flight from Tallinn to be on board a ship in Amsterdam on 2 September, from where he was due to sail on to South America. On his departure, Kalep was sad because this time he was not accompanied by a crowd.”

Before the plane goes, the Võhma ham goes

On the return flight, Elvy was so captivated by the beauty of his homeland that he decided to land near Võhma on the land of the Sagevere farm (now the territory of Kabala parish). The landing of the plane instantly set the whole area abuzz. Hundreds of curious onlookers from Võhma and Ollepa, and even from villages further afield, came to see the rare steel bird and its pilot. Elvy was shown the local sights, given a gift of smoked ham at the Võhma Export Chamber and butter at the dairy cooperative. In the evening, the brave female pilot was greeted by the chief of the Pilistvere militia, the chairman of the Võhma volunteer fire brigade, representatives of the Women’s National Guard and other social organisations. The female pilot was also very well received by the family of Doctor Hans Männik at the Tõnu farm. For the night, the plane was placed in a hayloft, which was guarded by members of the Defence League. From the grounds of the Tõnu farm, Elvy continued its flight to Riga the next morning. This time, she was accompanied by a large crowd.

Arnold Sepp, a journalist from Sakala at the time, recalled the day in his book “Mu meelen” (My Mind) as follows. So fly over! The last phrase, however, had nothing of the sledging quality of wording, because we had a Klemm-Hirth single-seat sports plane always ready to fly at Viljandi airport and our friend Ulrich Brasche, a pilot, lived just halfway between Sakala and the airport.

We immediately informed Brasche of the story, who of course was extremely enthusiastic and less than an hour after the call we too landed next to Elvy Kalep’s plane behind Männik’s barn. Or rather, Elvy’s plane had already been pushed into the barn and the spotting took place at the barn gate. With its wings folded in the barn, the Kalepi plane resembled a sleeping butterfly. Kalep surprised us with his exemplary Estonian. As if in an irony of fate, the Reds built an airfield on the farm land there in 1940-1941.”

Arnold Sepp remembered Kalep many years later in the newspaper Vaba Eesti Sõna: “Twenty-five years to the day when those certain planes landed behind the barn of Männiku in Võhma, a “familiar woman” accompanied by a former Estonian air force soldier, now a long-time resident of Miami, August Mihki, entered the Estonian House in Miami for one of the raids. The latter started to introduce the lady, but we were already looking at each other with glances that what’s there to introduce, we are already acquainted. The warm chatting got under way and stories about flights and the Võhma region were flowing. The flying lady had lost none of her youthful charm, nor her fluent Estonian. What particularly stuck in my mind from this second meeting and conversation was Elvy Kalep’s impetuous story of how the Germans of the Võhma Eksporttapamaja had given her a large censer on her departure. Later, flying somewhere in Europe, Elvy was a little short of money and had to sell the plane to get back to America by ship. “But that incense, I wouldn’t have sold it for anything!” the lady assured him with sparkling eyes. “I didn’t dare eat it, even though my stomach was empty. The other smelled so sweetly of the familiar Estonian farmhouse tare that I’d rather go by plane than this Võhma ham. So I brought the ham to America and it was only here, in the course of the festivities, that it began its natural shrinking process until it ran out somewhere around Chicago.”

Fate brings Elvy Kalep to America

The journey to the Americas was delayed. In 1931, the young female pilot sold her plane to the Shell oil company and emigrated to the Netherlands. On 10 May 1932, Elvy arrived from France to New York on the steamer Paris.

In America, Elvy became friends with Amelia Earhart (1897-1937), a famous female aviator who had already flown across the Atlantic with Slim Gordon and Wilmar Stultz in 1928. She also became good friends with the pilot Wiley Post (1899-1935), who died in a plane crash with his friend and comedian Will Rogers near Alaska in 1935. Writer of witty aphorisms, Will Rogers’ maxim: ‘Better a ghastly ending than endless horror’ proved true for him this time. Post had made his first solo flight around the world in 1933 in 7 days and 18 hours.

On 21 May 1932, Estonian globetrotters, aviator Elvy Kalep and ocean voyager Ahto Valter, along with his brother Jariilo, met at a dinner at the New York Education Society House in honor of the occasion. They had once again crossed the Atlantic Ocean. Perhaps it was there that Elvy had the idea of crossing the Atlantic by plane. In 1932, in New York, she was making serious preparations to become the first woman to attempt to cross the Atlantic alone. When her friend Earhart secretly completed her preparations three days earlier and became the first woman to fly across the Atlantic in 14 hours and 56 minutes in May 1932, Elvy Kalep decided there was no point in repeating the attempt as the second woman. She did, however, join 99 other women in America interested in aviation who had founded the Ninety-Nines in 1929 (by number of founding members), of which Amelia Earhart was the first president. Today, it is an international organisation of nearly 6,500 women pilots from 35 countries around the world.

Kalep had another big oceanic flight planned. On 15 August, she was due to take off with pilot Roger Q. Fischer. On August 15, she was due to fly from Los Angeles to Athens in honour of the Olympic Games with Roger Cape Williams (1895-1976). Initially, he planned to fly to Estonia, but could not find sponsors. The planned epic race was reported in all the major American newspapers, but then it turned out that the race was cancelled. Instead, the newspapers reported that Elvy Kalep had married stockbroker W. E. Hutton-Miller, who was categorically against the trip.

In Estonia, Kalep was somehow thought to be a millionaire and began receiving letters from benefactors. The letters were sent to New York airport and arrived. Elvy felt that “this kind of assistance is harmful because they are morally corrupting a person. A person has to manage his own life.” He stayed true to this principle even when he needed help later.

At the time, flying was still very dangerous. In 1919-1930, 28 people had died in attempts to fly across the Atlantic.In 1931, Earhart tried to fly a helicopter across America, but failed. In 1937, Earhart, who had set dozens of records, attempted to circle the globe around the equator, but was lost over the Pacific Ocean in early July with navigator Fred Noonan. There are many legends about his disappearance, and the exact place of his death is not known. Amelia Earhart wrote the following prophetic lines to her husband, the publisher George P. Putnam, before her final ascent. I am doing this simply because I want to. Women, too, must strive to do something like men. And if they fail, the failed attempt is a challenge to others.”

Elvy Kalep was probably motivated by the same thoughts.

Trouble is the best teacher

Instead of flying, Elvy Kalep started giving lectures about Estonia and aviation. In the early 1970s, she recalled: “I used to talk to Americans about everything, and when they asked me what the Estonian language sounded like, I would always declaim, ‘When the people of Kungla on the golden aal…'”. the first verse, which I think best describes the beauty of the Estonian language. The Americans loved it.” As an indirect result of his lectures, his first children’s book, Air babies (H.R.), starring his sister and brother Speedy and Happy Wings, was published in 1936 and illustrated by himself. About her book, Elvy Kalep later said that she wrote it with the aim of eliminating prejudice and fear of flying in young people, especially in parents who discourage young people. For some reason she was not happy with the illustrations in her book and, when all 100 000 books had been sold, she cancelled the contract with the publisher. A second edition was published in 1938 and a third in 2003. However, Kalep’s characters were so popular in America that they were even made into wallpaper in America. Even today, offers and requests to buy the book can be found on the Internet.

In a message, friend Amelia Earhart wrote, among other things, “When I recently did a survey of children’s aviation literature, I found that, unfortunately, very little was written for young people. Anyone who has worked in the industry will know that, of the whole population, it is the youth groups that are very important when it comes to aircraft and air travel. I hope that Air Babies and kids can become good friends”.

57 dollars

- World War II, which began in 1999, had put an end to some European subsidies, his marriage to a stockbroker had ended, and as Kalep had only $57 in his wallet on the day Britain declared war on Germany on September 3, he had to look for more permanent employment. The idea of providing children with something related to the age of aerial bombardment was a delightful one, and so Kalep launched the Patsie Parachute, a small parachute doll that dropped gracefully and wonderfully into the air.

This was the beginning of Kalep’s new business, which made him a household name in New York. He himself commented on it rather modestly: “I think up silly things and take the patents on them and give them to industrialists or produce them myself. Is there more money in the world given out for anything else than pleasant follies?”

The factory near New York, which employed 60 women, did not, however, make much money. Since there were no men available to work in the industry during the war, the tragic factory had to carry its own heavy burdens. Overworked, Kalep fell ill and was forbidden by his doctor to lift heavy packages. Finally, in 1946, he had to close the doll factory. The factory owner himself, however, had to take steps to improve his overstrained health and recuperate. All the money he earned was spent on health insurance. By 1950, he had recovered and was inventing new things, taking out patents on them and sending them to thousands of shops for sale. Among the latter was F.A.O., New York’s largest children’s toy store. Schwarz on Fifth Avenue, one of the windows of which is completely decorated with Elvy Kalep’s new dolls, the so-called Scribbles dolls, whose faces can be drawn by any child and re-drawn as needed.

Kalep told the story of how he came up with this new best-selling doll in 1950. After the doll factory closed down after the dolls were no longer made, I started to draw faces on them as a pastime. Because of a pencil problem, I started to erase the drawing on one of the faces, and the idea suddenly crossed my mind: why not let the children do it themselves? And now they can do it. With the doll, each child gets 5 crayons, an eraser and a “learning book” from the shop. With these tools, each child can give their doll a 1000 different looks on its face.”

Elvy Kalep is back in full creative and working mode. Her dolls are in the spring catalogue of the popular company Schwarz. Her pace of life is frantic, interspersed with interviews for newspapers, radio and television. The energetic lady was already thinking of setting up a new factory. The latter, however, did not materialise.

Little is heard of her in the years that follow. It is not known exactly when Kalep stopped flying. However, her traces did not disappear for good.

Lone wolf

- In 2008, The Arlington News published a long story about female aviator Elvy Kalep. In the same year, Pedro Krusten also wrote about her in Vaba Eesti Sõna. We learn that she is still proud and independent, and not looking for help from welfare. While living in California in 1960, acquaintances gave him five pieces of leather, all of which were his own colour. They added that she was a clever woman and maybe she could make something out of them. Maybe a pair of glasses. Elvy initially put the pieces of leather under the bed because she wasn’t interested in making glasses. Halfway through, a colourful mosaic popped into her mind’s eye: a Mexican, a cactus…. The next morning, someone gave him a piece of cardboard and some glue, and the night vision became reality. He liked the image and decided to take up a new hobby for a living. He trained for a year and then took out a patent on his invention. In 1967, still without a home, he travelled around America, exhibiting his work in expensive clubs, because experience had shown that he could only find buyers for his work among the rich. You can read Pedro Krusten’s story: “At the library in Arlington, his hand did not go well. He cancelled the courses he had advertised because there was no interest in them.We took his pictures from the glass case and took them outside, where his station wagon was parked. In the large vehicle, there was only room for him to sit. All the rest was taken up by his possessions, which were under the carpets. Mostly pictures. He brought out a large dragon. “My fifth job like this,” he said. “The first four have found a buyer, though. The price is two thousand dollars.” Of pieces of skin from lizards and worms. Very beautiful colours. He orders the skins from Europe. “I’m like a gypsy,” he says as he starts the car. “A lone wolf,” I thought, “proud and independent.”” Because of his declining health, in November 1986 he moved to the Regency Health Care Center (a so-called “retirement hotel”). He had no contact with his fellow countrymen for the past few decades, although he considered himself a good Estonian. Elvy Kalep died in Lake Worth (Palm Beach, Florida) on August 15, 1989. She had no relatives in the USA. He was buried alone, forgotten, but with the hope that perhaps he would be remembered in his native Estonia.